Maps

This is a work in

progress

Last update 8/12/06

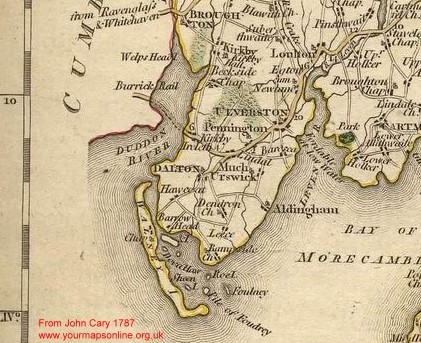

Even as a twelve year old, I loved maps so it was natural for me to turn to maps to try to find out why so many people worked in the mines - and why the mines all vanished again. And being into computers, I naturally turned to the Web to supply the information. I was pleasantly surprised at the number of old maps you can find on-line (even if some of the quality is not great), and I have pulled extracts out of most of the better ones on these pages. Click on any of the extracts to see the original source pages.

The Furness peninsula is an area of reasonably fertile land which is

bounded by the rivers Duddon and

Leven and the southern edges of the Lake District. This made it an

ideal place for an Abbey, but meant the industrial revolution was somewhat

late in arriving. The areas of sand and mud restricted access for large

ships, with quays limited to one at Ulverstone and one at the Pile of

Foudrey (Roa Island). Small boats could also get up to Kirkby Pool, and this was

the original transport route for the Burlington Slate Company which

supplied slate to the expanding towns of Manchester and Liverpool.

The

first sign of the Burlington quarry is on Greenwood's map of 1818, but

this was simply the first large scale exploitation. Looking at a

larger scale map, eg the Ordinance Survey 1 inch map from around 1850,

shows small slate quarries scattered the length and breadth of Swarthmoor.

Those shown in this extract are just above Moor Side at the South end of

the moor.

The

first sign of the Burlington quarry is on Greenwood's map of 1818, but

this was simply the first large scale exploitation. Looking at a

larger scale map, eg the Ordinance Survey 1 inch map from around 1850,

shows small slate quarries scattered the length and breadth of Swarthmoor.

Those shown in this extract are just above Moor Side at the South end of

the moor.

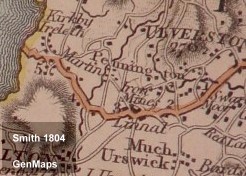

There was also a small iron industry using the very high quality iron ore

found locally - this giving the local stone it's deep red colour. The

ore was often overlain with a layer of limestone, which with wood  from the

local forests provided the basic raw materials for smelting iron.

The monks of Furness Abbey worked this iron, and the first mention of iron mines

on a map predates Burlington's quarry by

thirty years when Yates identified them near Lindal in 1786. In

1804 Smith also showed these mines - but managed to mis-spell the village

from the

local forests provided the basic raw materials for smelting iron.

The monks of Furness Abbey worked this iron, and the first mention of iron mines

on a map predates Burlington's quarry by

thirty years when Yates identified them near Lindal in 1786. In

1804 Smith also showed these mines - but managed to mis-spell the village name. Again, the extract from the OS 1850 map shows one of these

mines, and reveals that not only was the ore mined (as shown by the

shafts), but it was also an iron works and probably used limestone dug

from a pit right in the middle of the works. The presence of a

smithy reflects that horses were still the main source of motive

power. There is a reference on the Lindal web site (in Harrison Ainslie's Shipping Interests)

to the Whitriggs Horse Level, suggesting horses

were used underground at this mine and probably at others in the

area. See the Lindal

and Marton Community Website for this and other information about the area.

name. Again, the extract from the OS 1850 map shows one of these

mines, and reveals that not only was the ore mined (as shown by the

shafts), but it was also an iron works and probably used limestone dug

from a pit right in the middle of the works. The presence of a

smithy reflects that horses were still the main source of motive

power. There is a reference on the Lindal web site (in Harrison Ainslie's Shipping Interests)

to the Whitriggs Horse Level, suggesting horses

were used underground at this mine and probably at others in the

area. See the Lindal

and Marton Community Website for this and other information about the area.

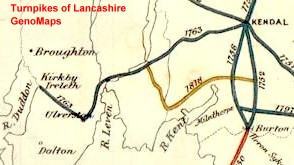

Further evidence that horse and foot were the main ways of travel is

shown by the route of the turnpikes. The

original land-based transport routes relied on crossing the sands, from Slyne (Hest

Bank) to Cartmel, from Lower Holker to Ulverston, and from Ireleth

to Millom. The  Lune

and Leven estuaries were largely mud flats, not really suitable for heavy

loads, so the original turnpikes ran up the Leven to Newby Bridge then cut

across to Kendal (lots of hills), or headed more South to Lindale (one big

hill) then across towards Milnthorpe (nice and flat). Anybody

approaching Furness on the A590 should recognise this route - apart from

the bypasses and diversions, it still follows the line of the 1818

turnpike.

Lune

and Leven estuaries were largely mud flats, not really suitable for heavy

loads, so the original turnpikes ran up the Leven to Newby Bridge then cut

across to Kendal (lots of hills), or headed more South to Lindale (one big

hill) then across towards Milnthorpe (nice and flat). Anybody

approaching Furness on the A590 should recognise this route - apart from

the bypasses and diversions, it still follows the line of the 1818

turnpike.

Despite what's shown on the map above, the turnpike did not turn

sharply right in Ulverston but in reality ran down to Lindal before heading across to Ireleth and straight

over the sands to Millom. This saved a day's

travel compared with walking up to Duddon Bridge, and the sand was firm

enough to take a carriage or cart. This shows up

in John Cary's map of 1787 which also shows the path ('fordable at low

water') across the Leven estuary.

reality ran down to Lindal before heading across to Ireleth and straight

over the sands to Millom. This saved a day's

travel compared with walking up to Duddon Bridge, and the sand was firm

enough to take a carriage or cart. This shows up

in John Cary's map of 1787 which also shows the path ('fordable at low

water') across the Leven estuary.

This map also shows the relative importance of Aldingham and 'Much Urswick', especially when compared with Barrow which at that time was an island rather than a town. Barrow started growing as a town when the railways arrived and started demanding steel by the mile. Furness had the high quality iron ore and the limestone to produce that steel - yet strangely the first railway bypassed Barrow for the more traditional harbour at 'the Pile of Foudrey' or Piel Channel as it's more commonly known these days.

Interesting Links

Lancashire County Council Maps

out

into the deep water channel allowing bigger ships to carry more slate and

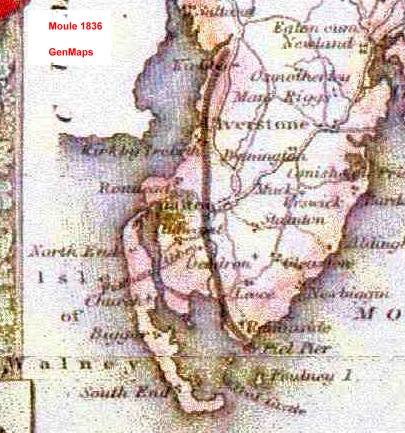

ore. The general course of this railway can be seen on Moule's map

of 1836 although I think this was sketched in rather than being surveyed in

any detail. The mapmaker also got confused at the South end, because

there is only one island shown between Rampside and Walney (positioned

nearer to the proper location of Roa), so he has drawn in 'Piel Pier' in

the middle of the mud flats.

out

into the deep water channel allowing bigger ships to carry more slate and

ore. The general course of this railway can be seen on Moule's map

of 1836 although I think this was sketched in rather than being surveyed in

any detail. The mapmaker also got confused at the South end, because

there is only one island shown between Rampside and Walney (positioned

nearer to the proper location of Roa), so he has drawn in 'Piel Pier' in

the middle of the mud flats.

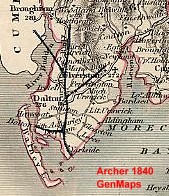

As the demand for iron increased the cost of transhipment from train to

boat became prohibitive, and by 1840 plans were in place to run a railway

from Carnforth (already on the main London to Glasgow line) through to

Furness and on to Millom, Workington and eventually through to

Carlisle. The biggest hold-up to this was bridging the three

estuaries - the Lune, Leven and Duddon.

As early as 1840, Archer was showing an expansion of this railway,

with branches to Ulverston and Barrow and an extensive viaduct across the

Duddon. As maps of that period always respected County boundaries,

we cannot say whether this line terminated at Millom or continued up the

Cumberland coast. We do know that the pressure was on the Furness railway to extend up the

coast - the Carlisle and Egremont railway had plans to extend South, so

the Furness laid it's own tracks from Egremont down to Millom ready for that viaduct.

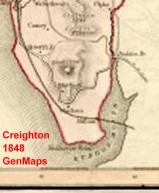

Creighton's map of Cumberland in 1848 shows this

line again with a viaduct, although now at a different (and more

realistic) angle.

Creighton's map of Cumberland in 1848 shows this

line again with a viaduct, although now at a different (and more

realistic) angle.

By about 1850, the viaduct had been abandoned in favour of a simpler

bridge further upstream, whilst the map by Wyld (which Barrow BC claim to

be '1840s') shows not only this bridge but also the two viaducts to

the East, and the railway connecting straight through to Carnforth .

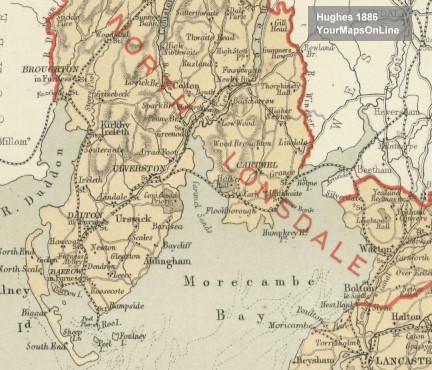

Unfortunately this map is too big to use here, so I have selected an

extract from a map by Hughes from 1886 which shows these lines and also

the Ulverston to Lakeside and the Broughton to Coniston lines.

.

Unfortunately this map is too big to use here, so I have selected an

extract from a map by Hughes from 1886 which shows these lines and also

the Ulverston to Lakeside and the Broughton to Coniston lines.

Whilst no doubt there were very good financial arguments for building it, the Lakeside line is often regarded as being James Schneiders private railway. After making his fortune from Iron, he moved into a large house at Bowness and commuted by steamer and railway to Barrow. The Broughton to Coniston line, on the other hand, was a working line mainly intended to bring slate down from the Coniston fells. It was also popular with visitors, attracted by Ruskin, and by Wordsworth's Daffodils. Wordsworth himself was against railways because they gave the working class access to beauty they could not appreciate - “Let then the beauty be undisfigured and the retirement unviolated” (Wordsworth's Arguments Against the Kendal and Windemere Railway)

We have wandered round Furness looking at railways, but haven't yet seen much of the family. Click here to see how they tie in together.